Triangular Book Cypher Text

Triangle Book Cypher Text

pg475

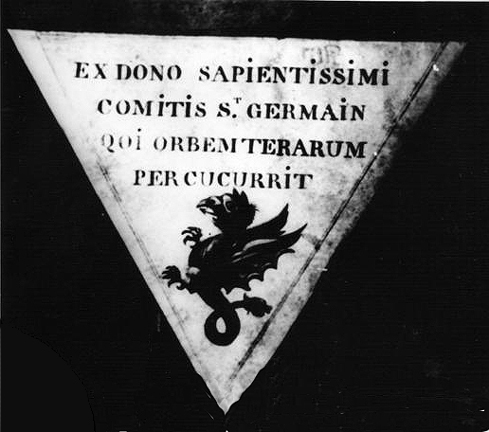

TRANSCRIPT OF A CURIOUS MANUSCRIPT WORK IN CYPHER,

SUPPOSED TO BE ASTROLOGICAL.

By PlIny Evute Chase

(Read before the American Philosophical Socicty, October 2d, 1873.)

The work, of which I have prepared the accompanying transcript, was bought in

"Ex Doxo S.vrtESTtsstMt Comttts St Germatn Qut Orrem TerRaRL-M PEUCUCURRIT."

The cypher consists of twenty-six arbitrary characters. In preparing to transcribe it, I counted the number of times each character was used, substituting a for the one that occurred most frequently, h for the next in frequency, and so on. The words are often run together, but there are numerous breaks, which I have indicated, some of which appear to mark divisions between words, whilo others may be arbitrary, or intended as blinds.

Sample Photo 1

Sample Photo 2

Sample Photo 3

Sample Photo 4

Sample Photo 5

Sample Photo 6

***

The most enjoyable dinner I had was with Madame de Gergi, who came with

the famous adventurer, known by the name of the Count de St. Germain.

This individual, instead of eating, talked from the beginning of the meal

to the end, and I followed his example in one respect as I did not eat,

but listened to him with the greatest attention. It may safely be said

that as a conversationalist he was unequalled.

St. Germain gave himself out for a marvel and always aimed at exciting

amazement, which he often succeeded in doing. He was scholar, linguist,

musician, and chemist, good-looking, and a perfect ladies' man. For

awhile he gave them paints and cosmetics; he flattered them, not that he

would make them young again (which he modestly confessed was beyond him)

but that their beauty would be preserved by means of a wash which, he

said, cost him a lot of money, but which he gave away freely.

He had contrived to gain the favour of Madame de Pompadour, who had

spoken about him to the king, for whom he had made a laboratory, in which

the monarch--a martyr to boredom--tried to find a little pleasure or

distraction, at all events, by making dyes. The king had given him a

suite of rooms at Chambord, and a hundred thousand francs for the

construction of a laboratory, and according to St. Germain the dyes

discovered by the king would have a materially beneficial influence on

the quality of French fabrics.

This extraordinary man, intended by nature to be the king of impostors

and quacks, would say in an easy, assured manner that he was three

hundred years old, that he knew the secret of the Universal Medicine,

that he possessed a mastery over nature, that he could melt diamonds,

professing himself capable of forming, out of ten or twelve small

diamonds, one large one of the finest water without any loss of weight.

All this, he said, was a mere trifle to him. Notwithstanding his

boastings, his bare-faced lies, and his manifold eccentricities, I cannot

say I thought him offensive. In spite of my knowledge of what he was and

in spite of my own feelings, I thought him an astonishing man as he was

always astonishing me. I shall have something more to say of this

character further on.

When Madame d'Urfe had introduced me to all her friends, I told her that

I would dine with her whenever she wished, but that with the exception of

her relations and St. Germain, whose wild talk amused me, I should prefer

her to invite no company. St. Germain often dined with the best society

in the capital, but he never ate anything, saying that he was kept alive

by mysterious food known only to himself. One soon got used to his

eccentricities, but not to his wonderful flow of words which made him the

soul of whatever company he was in.

By this time I had fathomed all the depths of Madame d'Urfe's character.

She firmly believed me to be an adept of the first order, making use of

another name for purposes of my own; and five or six weeks later she was

confirmed in this wild idea on her asking me if I had diciphered the

manuscript which pretended to explain the Magnum Opus.

"Yes," said I, "I have deciphered it, and consequently read it, and I now

beg to return it you with my word of honour that I have not made a copy;

in fact, I found nothing in it that I did not know before."

"Without the key you mean, but of course you could never find out that."

"Shall I tell you the key?"

"Pray do so."

I gave her the word, which belonged to no language that I know of, and

the marchioness was quite thunderstruck.

"This is too amazing," said she; "I thought myself the sole possessor of

that mysterious word--for I had never written it down, laying it up in my

memory--and I am sure I have never told anyone of it."

I might have informed her that the calculation which enabled me to

decipher the manuscript furnished me also with the key, but the whim took

me to tell her that a spirit had revealed it to me. This foolish tale

completed my mastery over this truly learned and sensible woman on

everything but her hobby. This false confidence gave me an immense

ascendancy over Madame d'Urfe, and I often abused my power over her. Now

that I am no longer the victim of those illusions which pursued me

throughout my life, I blush at the remembrance of my conduct, and the

penance I impose on myself is to tell the whole truth, and to extenuate

nothing in these Memoirs.

The wildest notion in the good marchioness's brain was a firm belief in

the possibility of communication between mortals and elementary spirits.

She would have given all her goods to attain to such communication, and

she had several times been deceived by impostors who made her believe

that she attained her aim.

"I did not think," said she, sadly, "that your spirit would have been

able to force mine to reveal my secrets."

"There was no need to force your spirit, madam, as mine knows all things

of his own power."

"Does he know the inmost secrets of my soul?"

"Certainly, and if I ask him he is forced to disclose all to me."

"Can you ask him when you like?"

"Oh, yes! provided I have paper and ink. I can even ask him questions

through you by telling you his name."

"And will you tell it me?"

"I can do what I say; and, to convince you, his name is Paralis. Ask him

a simple question in writing, as you would ask a common mortal. Ask him,

for instance, how I deciphered your manuscript, and you shall see I will

compel him to answer you."

Trembling with joy, Madame d'Urfe put her question, expressed it in

numbers, then following my method in pyramid shape; and I made her

extract the answer, which she wrote down in letters. At first she only

obtained consonants, but by a second process which supplied the vowels

she received a clear and sufficient answer. Her every feature expressed

astonishment, for she had drawn from the pyramid the word which was the

key to her manuscript. I left her, carrying with me her heart, her soul,

her mind, and all the common sense which she had left.